14 SEO Tips to increase traffic and rankings

February 12, 2019

Recipe for Daddy’s Outta Sight Tagine

February 21, 2019The following article is the third in a series about our family’s experiments in alternative education. See Part I: A year without a principal and Part II: Out of the classroom and into the wild.

When we left off last, our family was looking for a place to settle down after spending a year as work-exchange volunteers in 12 different households between Germany, Austria, France and Spain. Based on an elaborate set of criteria that factored in things like climate, geography, cultural composition, and access to zen, we’d narrowed our sights down to the Black Forest region of southwest Germany and the Cerdanya region of the Spanish Pyrenees.

At this point, our top priority was to find a school, or some sort of pedagogic alternative, that would offer the kind of freedom and flexibility that we had come to value. Our ongoing research and experimentation had convinced us that education was moving in a new direction, and we very much wanted to be at the forefront of that movement.

A lesson in cultural contrasts

As we studied our options, we quickly saw that the distinctions between the Spanish and German school systems—at least insofar as we came to understand them—perfectly encapsulated the differences between Spanish and German cultures as a whole.

A land of law and order, Germany has a proper system and a series of rules for everything. In regards to grade school education, German law requires every child to attend. The “Schulpflicht”, as they call it, effectively outlaws any form of homeschooling. But, as with most German policies, there is a procedure by which you can apply for an exemption. A specific form is obtainable and can be submitted to the designated office. Our own experience, however, led us to believe that the true role of this office was to review and systematically deny every application for exemption.

Don’t get me wrong. It’s not that I’m categorically opposed to law and order in all its guises. In fact, it’s impossible not to admire the reliability and efficiency of nearly all things German. Hop over from Germany to Spain for an afternoon, and just see much business you’re able to conduct.

For starters, you’ll find that most businesses aren’t even open. Generally, shops and offices close from around 1 till 4 p.m. But that’s a very rough estimate, and it’s pretty rare for a business to post its hours in the window. And when they do, it’s usually nothing more than just another rough estimate. They might not reopen till the next morning. And for all you know, there could be a major festival taking place in the next village over, in which case they won’t open again until next week.

Now in Germany, if there’s a protocol—and there almost always is—you can be certain that the officials will follow it to the letter. The procedure might not be simple, but it is clearly defined. When you want to understand the rules of engagement, or the process of obtaining a visa, this is great. But when you’re hoping for someone to cut you some slack or give you a little leeway, you may be strait out of luck.

In Spain, they too have rules and procedures, but no one seems to agree on what they are. If you’re a smooth talker, this can allow you to burrow through some pretty wide loopholes. But when you want to know what documents you need to establish residency, the requirements depend entirely on who’s sitting behind the desk that day and what kind of mood they’re in.

So trying to chose between Spain and Germany, you have a classic cultural conundrum. Do you want to bolt down the Autobahn with speed and precision, knowing that any failure to stay in the correct lane will result in deathly stares from every black Mercedes trying to set a new land speed record?

Or would you like to bounce along from one tapas bar to another, with leisurely nonchalance, never knowing which restaurant will be open and whether or not they’ll be sold out of your favorite seafood platter?

The trouble, for me anyway, is that some days I’m in a big hurry, very much in line with Germany’s diligent work ethic. But other times, I just want to drop what I’m doing, postpone everything, and disappear on a week-long road trip through beaches and countryside. That’s right, I want to have my Black Forest cake and eat it too.

On the one hand, I want it all: I want the best of both worlds. But at the same time, I really do appreciate the distinct character that each culture embodies. The North American melting pot is all well and good, but there’s something uniquely satisfying about sinking your teeth into that standout dish with an undeniable flavor of its own.

What does all this mean for our educational options?

Most of Europe, as we learned, enforces obligatory schooling or permits some narrowly regulated version of homeschooling. In orderly Germany, they have the Schulpflicht. But surely the easy-going Spaniards must allow informal homeschooling, right? Indeed, homeschooling is not illegal in Spain. It is, however, a-legal. No, we don’t even have a word for that in English. And I can’t begin to imagine how the Germans would feel about such an ambiguous status.

Because homeschooling is not illegal, there is no need to apply for special permission. But because it is not actually recognized, there are no guidelines or curriculums to follow. And yet, because it’s not entirely legal, you still don’t want everyone to know you’re doing it. At the end of the day, nobody really knows how or whether you might be punished if you got caught.

Spain is still about 20 years behind the U.S. in a lot of ways, so maybe it’s not such a surprise to see them using the Don’t Ask Don’t Tell policy. But where does that leave us? Practically speaking, homeschooling is pretty uncommon in Spain. At least it’s not commonly seen. Those who venture into this grey area seem to do so privately. And as far as we’re concerned, that really defeats the purpose of homeschooling when the kids have to effectively hide out in the house all day trying to avoid social interaction.

German possibilities

In an effort to be thorough, we took another look at Germany. Rigorous and regulated as the country might be, Germans are somewhat famous for their philosophical traditions and their unconventional subcultures. As it turns out, Montessori education is fairly popular in Germany, as are Steiner or Waldorf schools, as well as democratic schools. In most cases, these and other alternative style schools are private and tuition based, but the prices can vary dramatically, often based on a sliding scale.

So we began researching democratic schools in the state of Baden-Wurttemberg, and to our surprise, we found quite a few. Essentially, the democratic school model is based on the principle of self-determination and recognizing students and teachers as equals. Summerhill School in England and the Sudbury Valley School in Massachusetts are the leading exemplars of this model, and Germany has a growing number of smaller schools who embrace this concept.

But if you think that enrolling in an alternative-style school will allow you to escape the Teutonic grip of obligatory, standardized education, you’ll be in for a bit of a disappointment. Even the schools that identify with a very specific pedagogical philosophy must operate within the boundaries of a very carefully spelled-out system. So a Montessori school, for example, cannot follow every aspect of the Montessori method. Instead they can really only claim to be teaching in the style or the spirit of Maria Montessori.

But, believe it or not, we aren’t actually fanatical adherents to one strict methodology or another. We’re just looking for something a little less structured and more openminded. So we went ahead and put our kids on the waiting list at a handful of democratic academies in the vicinity of Freiburg and Stuttgart. It turns out these alternative schools are actually very popular, and still too small to meet the growing demand of forward-thinking families.

The most attractive schools naturally had the longest waiting lists, suggesting that our kids would most likely not be able to enroll in the next school year. And looking at some of the other schools, we discovered they too had succumbed to the German tradition of relentless rule making. I have no problem with a school that doesn’t allow iPads in the classroom. It seems perfectly reasonable. But to extend that prohibition and forbid the kids from ever using a touchscreen device, even at home, before the age of 12, was going a bit too far. What sort of world is that supposed to prepare them for?

Into the wild

And so, overwhelmed by rules and regulations, and unable to overcome the affordable housing shortage in the Baden-Wurttemberg region, we ventured back down to the Spanish Pyrenees where a good friend had offered us an apartment space behind a derelict hotel on a spectacular piece of property. The offer and the alpine setting were simply too good to pass up. And meanwhile, our search for a school continued.

A high plateau on the French-Spanish border, the Cerdanya combines the languages and cultures of Spain, France and Catalonia. The two largest towns have about 10-15,000 inhabitants, and most of the region’s population is spread out across dozens of small stone villages that punctuate the sweeping pastures and rugged mountains. To the nearest real city, Barcelona, it’s about three hours by train. In other words, the area is beautiful in many ways, but a cosmopolitan population center it is not.

If we had just one word to describe our new setting in the Pyrenees, it would be remote. Visitors have had a hard time finding us here. Even the mailman has a hard time finding us. And without making the trek to Barcelona, there are a considerable number of urban conveniences that we just cannot access from our remote location on the frontier. And what about our chances of finding the right school, of assimilating with the local culture, and of finding economic opportunities? Remote, remote, remote.

And yet here we are. And we’re still not sure if we found it, or if it found us. Just five minutes from our remote hideaway behind the old hotel and spa, we discovered one of the best kept secrets in the Cerdanya. But the secret is spreading quickly. In fact, families are coming from greater and greater distances to live in the tiny village of Montella de Cadí, for no other reason than to attend this unique school.

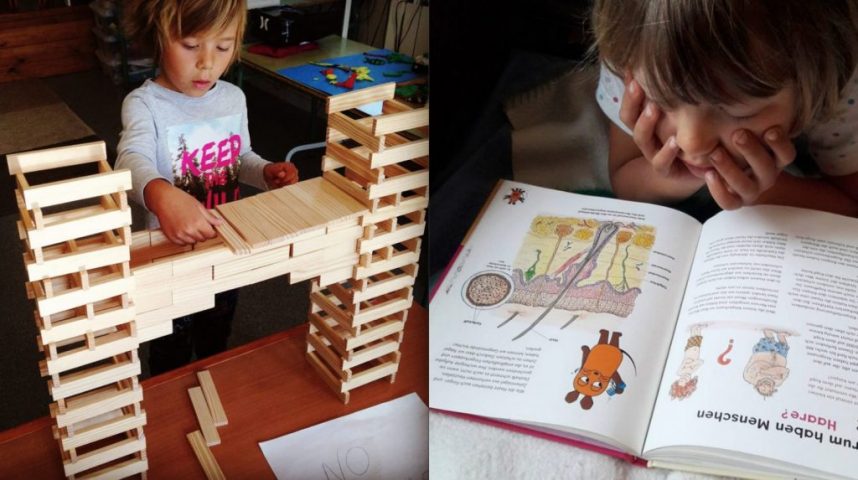

With just five teachers and about 40 students, ranging from 3 to 11 years in age, the school incorporates the ideas of Steiner, Montessori and democratic education to provide a learning environment like none we’ve ever seen. The different ages work and play together for a part of the day, and then break up into three or four different age groups for various lessons and self-directed projects. Catalan is the primary language of the school, but one teacher speaks English most of the day while another speaks mostly Spanish. A French teacher also comes in every Thursday. At least once a week, the school goes out into the forest or to a nearby village to study the local history and natural habitats. The forests and landscape of the Pyrenees are exceptionally diverse.

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of all, is how we wandered the continent for a year, finally stumbling upon a remote mountain village, only to discover this amazing community of families who think more or less like we do. They certainly value the same type of education.

When we first brought our kids to the school for a half-day trial run, almost two years ago, they refused to leave. And this was even before they could speak a word of Catalan. They spent the whole day at school, and insisted on coming back the next day, and for the following two weeks until the end of the term. At that point, of course, we went ahead and enrolled.

No one came from as far away as we did to attend the school, but it is definitively attracting interest from all across Catalonia and Spain. Meanwhile, always reluctant to adapt, the government only creates more obstacles for this maverick institution. It is not a private school, but a public one, which the officials barely tolerate.

Rather than placating the demand by making it easier for the school to grow and for outsiders to enroll, the state recently went the other direction and tightened admission requirements. New students cannot enroll without having an address in this tiny village. As it is, the village only has about 100 residents, and rents are almost triple what they are in neighboring villages, only because the school has created such a staggering demand on the local housing market. In most cases, families are turned away or forced to resort to more questionable means of registration.

Where do we go from here?

If there’s a single dark cloud hanging over this piece of paradise, it’s the lingering question of where to send the students when they finish sixth grade. Not that this school divides children into grades per se, but at the age of 11 or 12 they have to transfer to a secondary school. And the options in this region are nothing but the most ordinary and conventional. Some students make a smooth transition, but others are stupefied by the inundation of meaningless busy work and the factory-like arrangement of desks.

Again, it’s not the worst place to send a child. As far as filling their minds with rudimentary facts and preparing them to sit for a university entrance exam, the traditional schools seem to get the job done. But when it comes time to unlock their imaginations, to discover their passions, and to explore unchartered territories, the opportunities rarely arise.

Most of what I remember from secondary school was completing one assignment after another, cramming for the next test, and spoon feeding the facts and figures back to my instructors as pleasantly as possible, never pausing for a moment consider how these exercises would serve me beyond the close confines of the classroom. And I graduated valedictorian. But after graduation, I didn’t have the vaguest idea what to do with myself.

I don’t know where our children will go when they outgrown their current school. Perhaps we’ll head to the Green School in Bali, Indonesia. Or maybe we can work with the local community to build the kind of secondary school that our friends and neighbors clearly want. There’s no doubt it will fill up quickly if we can put it together. Our children want it, their classmates want it, and the families who couldn’t move to Montella want it. And, after all, what better use could their be for a derelict hotel and spa on the stunning slopes of the Pyrenees?

So with any luck, there will be a future sequel to this series, in which I recount the tale of how we all came together as a community and worked to build the school of our dreams, a school that truly addresses the enormous challenges and opportunities of our rapidly changing planet.

FURTHER READING: To learn more about our ongoing adventures in education and cultural assimilation, check out some of the following articles.

2 Comments

I love your writing style, it’s funny, anecdotal and interesting. I’m just learning about word schooling (and all the other various names) and it’s so fascinating. My little guy has just turned one and we are on our path to financial independence so I’m looking forward to reading on to find out more about your journey and be inspired to do something similar ourselves in a few years!

Thanks for the feedback. So glad you enjoyed it. Best of luck in all your journeys!